Workers, Peasant and Tribal Movements in Bihar

The peasant movements for agrarian reforms in India have always been centred on the issue of land ownership and land distribution. The term ‘peasant’ includes tenant, sharecropper, small farmer not regularly employed, hired labour, and landless labourers. Several peasant movements rose over economic questions all through the British period but with limited results. The 20th century saw some of the most violent and widespread peasant movements with far-reaching consequences. The main demands of these movements centred on reduction of excessive rent or revenue on produce and land redistribution from the rich to the poor. Many of these movements have provided the stimulus necessary for land legislation in India.

The Santhal Insurrection (Tribal Movement):

The Santhals are an agricultural tribal group who are mainly concentrated in Bihar. The first peasant insurrection took place in 1855-1856, which arose due to the establishment of the Permanent Land Settlement of 1793. Following this settlement the Britishers took away all the lands from the Santhals. The zamindars took these lands on auction from the Britishers and gave them to the peasants for cultivation.

The zamindars, the moneylenders, and the government officers hiked the land tax and also oppressed and exploited the common peasants. Though the Santhals tolerated the injustices to some extent, later on they decided to raise in revolt against the zamindars, moneylenders, and traders.

The following were some of the main causes of the revolt:

- There was a combined action of extortions by the zamindars, the police, the revenue, and the court. The Santhals had no option but to pay all the taxes and levies. They were abused and dispossessed of their own property.

- The Karendias who were the representatives of the Zamindars made several violent attacks on the Santhals.

- The rich peasants confiscated all the property, lands, and cattle of the Santhals.

- The moneylenders charged exorbitant rates of interest. The Santhals called the moneylenders exploiters and were known as “dikus”.

- For the railroad construction, the Europeans employed the Santhals for which they paid nothing to them. The Europeans often abducted the Santhal women and even murdered them. There were also certain other unjust acts of oppression.

The oppression by the moneylender, zamindars, and Europeans became unbearable by the Santhals. In such a situation, they did not have any other alternative indeed and they rose in rebellion. The leading Santhals began to rob the wealth of the moneylenders and the zamindars, which was ill-earned by exploiting the Santhals. Initially, the officials ignored the rebellion. Later on in early 1855, the Santhals started to build their own armies who were trained in guerilla fighting. This was totally a novel experience to the people of Bihar.

The Santhals can be praised with great honor for building such an organized and disciplined army without any previous military training. The large army, which exceeded about 10,000 assembled and disassembled at a short notice. The postal and railway communications were completely broken down by the Santhal army.

The government then realized that the activities of the Santhal army are defying the government. Though the Santhal insurrection was quite strong it couldn’t succeed against the power of the government. Thus, the revolt was suppressed. Despite the suppression, the rebelhon was a great success.

This was because the Santhals gave a message to the whole country to resist the oppressive activities of the moneylenders and zamindars. Not only the Santhals but the other agricultural tribal groups also got united. It brought a realization among the diku population that the Santhals were an organized group of people and possessed much enthusiasm.

The Britishers took appropriate measures after the Santhal insurrection. Earlier to the insurrection, the settlement areas of the Santhals were divided into several parts for administrative convenience. Due to the Santhal rebellion, the Santhal areas are considered as Santhal Paragana. Due to the insurrection, the Britishers recognized the tribal status of the Santhals and now they came under the uniform administration.

Peasant Movements in Bihar

Champaran Movement:

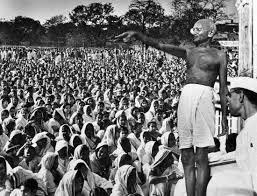

Champaran movement was the India’s first civil disobedience movement. A movement fought by farmers/peasants for their rights. Resurgence in the history of Bihar came during the struggle for India’s independence. It was from Bihar that Mahatma Gandhi launched his civil-disobedience movement, which ultimately led to India’s independence.

Champaran is a district in the state of Bihar. Under Colonial era laws, many tenant farmers were forced to grow some indigo on a portion of their land as a condition of their tenancy. This indigo was used to make dye. The Germans had invented a cheaper artificial dye so the demand for indigo fell. Some tenants paid more rent in return for being let off having to grow indigo. However, during the First World War the German dye ceased to be available and so indigo became

profitable again. Thus many tenants were once again forced to grow it on a portion of their land- as was required by their lease. Naturally, this created much anger and resentment.At the persistent request of a farmer, Raj Kumar Shukla, from the district of Champaran, in 1917 Gandhiji took a train ride to Motihari, the district headquarters of Champaran. Here he learned, first hand, the sad plight of the indigo farmers suffering under the oppressive rule of the British. Alarmed at the tumultuous reception Gandhiji received in Champaran, the British authorities served notice on him to leave the Province of Bihar. Gandhiji refused to comply, saying that as an Indian he was free to travel anywhere in his own country. For this act of defiance he was detained in the district jail at Motihari. From his jail cell, with the help of his friend from South Africa days, C. F. Andrews, Gandhiji managed to send letters to journalists and the Viceroy of India describing what he saw in Champaran, and made formal demands for the emancipation of these people. When produced in court, the Magistrate ordered him released, but on payment of bail. Gandhiji refused to pay the bail. Instead, he indicated his preference to remain in jail under arrest. Alarmed at the huge response Gandhiji was receiving from the people of Champaran, and intimidated by the knowledge that Gandhiji had already managed to inform the Viceroy of the mistreatment of the farmers by the British plantation owners, the magistrate set him free, without payment of any bail. This was the first instance of the success of civil-disobedience as a tool to win freedom. The British received, their first “object lesson” of the power of civil-disobedience. It also made the British authorities recognize, for the first time, Gandhiji as a national leader of some consequence. What Raj Kumar Shukla had started, and the massive response people of Champaran gave to Gandhiji, catapulted his reputation throughout India. Thus, in 1917, began a series of events in a remote corner of Bihar, which ultimately led to the freedom of India in 1947.

After the Champaran Satyagraha in 1917, Bihar became an important centre for peasant movements. These activities had addressed the problems of share croppers such as abolition of customary non-rent payments, regulation of eviction, and fixation of fair rent. The main centre of the movements was north Bihar. In North and Central Bihar, a peasant movement was an important side effect of the independence movement. The KisanSabha movement started in Bihar under the leadership of Swami SahajanandSaraswati who in 1927 had formed the Bihar Provincial KisanSabha (BPKS) to mobilise peasant grievances against the zamindari

attacks on their occupancy rights. Gradually the peasant movement intensified and spread across the rest of India. All these radical developments on the peasant front culminated in the formation of the All India KisanSabha (AIKS) at the Lucknow session of the Indian National Congress in April 1936, with Swami SahajanandSaraswati elected as its first President. This movement aimed at overthrowing the fedualzamindari system instituted by the British. It was led by Swami SahajanandSaraswati and his followers Pandit Yamuna Karjee, Rahul Sankrityayan and others. Pandit Yamuna Karjee along with Rahul Sankrityayan and other Hindi literaries started publishing a Hindi weekly Hunkar from Bihar in 1940. Hunkar later became the mouthpiece of the peasant movement and the agrarian movement in Bihar and was instrumental in spreading the movement. The peasant movement later spread to other parts of the country and helped in digging out the British roots in the Indian society by overthrowing the zamindari system.With passage of Zamindari Abolition Act, 1949, the movements disappeared. In 1978, the peasants in Bihar, under the leadership of the YuvaChhatraSangharshSamity, organized a long drawn out struggle in Bodhgaya to secure land rights from the Shankar Math. The Mahants (religious heads) of the Buddhist monasteries in the area had amassed huge tracts of land under the exemption given to religious and charitable institutions in the ceiling laws of the state. The situation erupted in violence. After the Supreme Court’s directive to the effect that the land is handed over to the tillers, the struggle was considered to be successful.

Towards the end of 1946, between 30 October and 7 November, a large-scale massacre of Muslims in Bihar made Partition more likely. Begun as a reprisal for the Noakhali riot, whose death toll had been greatly overstated in immediate reports, it was difficult for authorities to deal with because it was spread out over a large number of scattered villages, and the number of casualties was impossible to establish accurately: “According to a subsequent statement in the British Parliament, the death-toll amounted to 5,000.